After getting settled in the hostel there (Tango Hostel, great place), Sydney and Marco came by and we walked to have dinner and explore a little bit. We all had lomito, which is basically a thin strip of beef on a sandwich with any number of other things, usually ham and eggs. It's one of the many excellent Argentinian basics that I really love.

We walked around a fair for a while before heading to a local gay bar to see a drag show. Sydney and Marco awesomely agreed to give me some company and unfortunately had to put up with my poor directional skills; we got a little lost on the way to the bar. Getting lost is always interesting, however, and this particular detour gave me an opportunity to explore some of the graffiti in Cordoba. Graffiti here is almost always political and comes in several forms, sometimes stamps that can be reused and other times the more traditional scrawled words or pictures.

The bar was a dive in the good way, not super fancy and tucked into a little corner on the street. As the drag show started, we should have known that Sydney would get in trouble. The queen who was hosting complimented her hair and before we knew it, Sydney was on stage with several locals waiting to participate in a karaoke competition. Luckily, someone took her place, as Sydney knew none of the songs they gave as options, but she couldn't leave the stage before some small talk and dancing with the lovely host.

The bar was comfortable and the crowd was big without being overwhelming. I spoke to a trans woman who told me that she much preferred Cordoba to Buenos Aires and told me a little about her experience.

Argentina has what are probably the most liberal gender identity laws in the world. A trans person can go to the courthouse and change his or her gender on official documents without any kind of psych evaluation or medical treatment. While I was in Poland, I did some research for the KPH on trans rights, and I was, first of all really ignorant, but also really shocked at how many countries require extreme psychological or medical treatment, including sterilization, before allowing a trans person to change his or her documents.

Argentina is leading in the movement to stop treating trans identity like a medical disorder.

The next day, I spent a little time exploring the city and that night, Marco and his mom were nice enough to let me come by to pester her with questions. Lizi works in part in sexual education, and she was able to talk with me about the struggles with implementing the new sexual education laws in Argentina and about the issues of gender violence and sexual orientation in the curriculum. She has some great games and tools to show teachers how to talk about these issues in their classrooms, and she tries to be inclusive of every age, gender pairing, and body type. There's a memory game with pictures of various couples, and a condom is present somewhere in each picture. She has two anatomically correct dolls, one male and one female. The female is pregnant and includes a baby, umbilical cord and all, that can be removed. There are word games and group discussions about gender violence and self-respect.

Lizi told me that it's difficult to implement the new sexual education law for several reasons. First of all, it's difficult because people do not know what the law includes, so they do not teach what they should. Secondly, the resources for training teachers are limited, especially in the provinces. It's difficult to find the resources. There is also, apparently, some push back against the law, but here in Argentina, a national law trumps all, so there is nothing similar to a states' rights argument. It was fascinating and informative, and I'm so grateful to Lizi and to Marco and Sydney for letting me barge in, feeding me ice cream, and letting me stay way too late (sorry again about that).

Marco also introduced me to Churipan, which is, I suppose, sort of like an Argentinian equivalent to kabob in that it's something that you might grab late at night but is also really delicious.

The next day, I ate some pretty delicious empanadas with some folks from the hostel and later, Sydney and I explored the city a little with Kristal, who is from New Zealand. We walked around town, through the main square and down the central streets. There was a book fair celebrating thirty years of democracy in Argentina, and we explored the different stalls and tents.

The streets have the shadows of historical buildings constructed in stone

La Iglesia de Compania de Jesus. The architect was a boat builder, and that's obvious inside the church. See below.

El Papa

The ceiling, much like a boat.

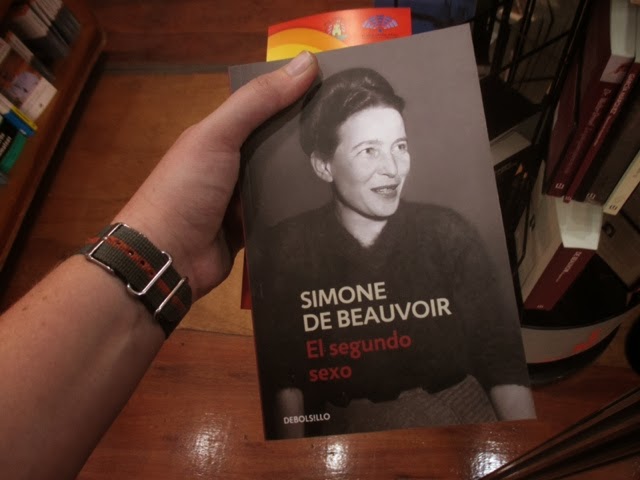

Familiar friends at the book fair.

That day the city was burning hot because fires were burning through the hills outside the suburbs. It had been a very dry season with little rain and suddenly the hills were literally on fire. Ash drifted down onto Cordoba like snowflakes, and the sky turned gray. As we walked through the city, we felt the hot air blowing against us like we had opened an oven.

The gray skies and some ash

As we continued exploring, Sydney introduced me to Alfojars, which are ridiculously sweet and yummy Argentinian candies/cookies/sweet things. There are two or three layers of a cake or cookie substance normally surrounded by dulce de leche, but sometimes chocolate or really any sweet thing, and then dipped in chocolate or white chocolate or another sweet coating. They are amazing, and we sat on a bench in the main square eating and drinking something cold.

Cool blooms in a tree in the city center

The main square, Plaza San Martin

Center of the Plaza

The mark of the Mothers in Cordoba

Kristal's bus for Buenos Aires left that night, so she had to head back to the hostel, but Sydney and I kept going for a bit. We found, after a long search, a waffle place and had delicious sandwiches folded into waffles instead of bread. We sat in front a fountain in the city and talked before Sydney went home that night.

Photos of desaparecidos still missing

My last day in Cordoba, I worked a little on my quarterly report (whoa, three months goes by quickly) and then Sydney and I went to visit a museum of the desaparecidos, called Museo de la Memoria. It is housed in the police station where those who were kidnapped were taken.

The outside of the museum is covered in large fingerprints made of the names of the disappeared.

The rooms are filled with history but also with token from the families of those who suffered there. One room has shelves of photo albums and letters, handwritten stories and accounts about those who died.

There are photographs salvaged from the site, although the architecture was changed at one point to disguise it. There is a tree of memory, reminiscent of the tree in Budapest for those murdered in the Holocaust.

I had to pack up and get ready for the bus, sadly, so Sydney and I had some ice cream and then said goodbye. It was so great to see her.

That night I hopped on a bus to Salta, although the bus companies were on strike, so that was quite an experience. My cab had to stop way outside the station, a police officer walked me to the desk of my bus company, and the lady there proceeded to tell me that a car would pick me up, I just needed to wait. Although I understood what she said literally, I had no idea what was happening or why a car would need to pick me up. A very nice man took pity and explained that there was a strike and made sure I got in one of the shuttles to my bus.

Apparently this is not out of the ordinary. There is always some kind of strike happening, it seems, and I love the political spirit in Buenos Aires and around the country. At times, though, it's far beyond my cultural or linguistic vocabulary to understand what is happening and why. For example, the woman at the counter who helped us was technically on strike, but there seemed to be an agreement between the union and the employees to maintain some kind of schedule. Anyway, I made the bus and was on the way to Salta.

I had contacted an LGBT organization in Cordoba but had not heard back; it was a last minute find and they did not have an address listed, so my hopes were not high. They got back to me and could not have been nicer, but I was gone before they had another meeting.

Since there were no physical addresses that I could find, it was difficult to determine where, outside of bars, things were happening. I imagine that the university is a site of community, but I could not find a contact. It did seem, however, like there was gay space, which was of course very different from the visit to Krakow, which has, on the surface, many similarities to Cordoba.

In Salta, I had two physical addresses to visit, which was really exciting. One was for a group called ATTTA, a trans organization that also has a branch in Buenos Aires. Another was for a lesbian group with an office in the center of the city.

My first day in Salta was a little strange. I took a cab from the bus station to the hostel; normally I walk but it was quite a distance, so I caved. By the end of the cab ride, however, I wished that I had walked. The cab driver was young and nice, but very quickly, questions veered into the possibly weird and too personal category. "Are you traveling alone? Is anyone going to be waiting for you? Do you know anyone here? Do your parents know where you are?" Of course these can be totally harmless questions but they can also mean not great things, so I was in the backseat trying to gauge what exactly was happening. To be safe, I just flat out lied. "Yes, my brother is here to visit me." As it turned out, he just took what was obviously an extended route to the hostel and overcharged me, but it was one of those moments when I was trying to think of what I might do to get out if I needed to. It's sometimes hard to tell the difference between paranoia in a new place and real possible problems, but as my friend Matthew told me in Warsaw one night when we left a party early together, "Those guys gave me the creeps. They were way too interested in the fact that I was traveling alone and it's always better to trust your instincts." I had heard one too many stories about unregistered cabs and robbery, and even though I had been in the "official" line at the bus station, that seemed to mean little to nothing. Anyway, it was all fine, but those moment are not my favorite.

For the rest of that day, I slept a little after a really awful bus ride (whoa bumpy. At more than one point, we were actually driving on dirt and rock.) and sent off my quarterly report. Feeling much better, I wandered over to visit ATTTA but arrived too early in the day; they weren't yet open. So I did some exploring in the meantime before returning that night.

I was in Salta during the celebration of the Miracle, so the streets were really crowded with visitors from throughout the province and even from Bolivia and a few other countries. The main church is in the center square of town, and volunteers handed out prayer books. The rosary was projected on a big screen outside and people prayed most of the afternoons and evenings while I was there.

The miracle of Salta goes something like this: four hundred years ago, there was a major earthquake in Salta. A priest there dreamed that if a statue of Christ, which had floated ashore as the only survivor in a shipwreck years before, then God would stop the quake. The next time a tremor hit, in the 20th century, the people paraded Christ as well other religious imagery through the streets, and the quake stopped. There has not been another one since. Every year, many people journey to Salta on foot to celebrate this miracle and pray.

The Basilica where pilgrims celebrate the miracle

Because the office of the other organization was very close, I popped in, but unfortunately, it was the office of the Socialist Party, and nobody was there to ask about a new address.

That evening I returned to the ATTA house and stumbled into a meeting of an HIV advocacy and support group. I apologized but they told me to sit down and gave me soda and birthday cake. I listened while they debated about what to name their organization. It was a fascinating conversation. One side wanted something overtly political, the other something more neutral. The neutral side won out in the end; it had more support and many people said that protecting the anonymity of those who wanted to participate without outing themselves obviously trumped the desire to make a political statement. The other side argued back that they were not ashamed and wanted to be able to be together and simultaneously make a statement about being open.

ATTTA house. I was nervous walking to find it because I had no idea what to expect and I was clearly in a residential area. I really didn't want to knock on a random door, but luckily there were signs in the window.

There was a lot more nuance going on, but my Spanish skills and the rapid exchange in the debate made it difficult for me to get specifics.

After the meeting, a very nice guy, Jose, called his friend, Enrique, who worked as a professor and was concerned with sexual education, and he came to speak to me. We chatted in Spanglish for a long time about Salta and LGBT life there.

He told me that many people in Salta never come out of the closet or, if they do, it's a one-time thing and nobody ever speaks of it again. Of course, same-sex marriage is legal there just like everywhere else in Argentina, but Enrique told me that same-sex couples would probably want or need to be very careful or travel in order to get married and celebrate. He himself lives with a partner and his family knows. He explained that hiding himself was not really an option; he needed to be open and free in order to feel like himself.

He also told me, much like Lizi, that there barriers when it comes to implementing the new sexual education law, and he sees pregnant teenagers walking around and in classes all the time. He says the influence of the Church is much stronger in the provinces than in Buenos Aires and also that Salta has a major problem with HIV. When I asked about LGBT social life, he told me that there are two bars, one of which is considered old because it has lasted more than seven years and the other which is fairly new and might die out, apparently a fairly common occurrence. Speaking about the older bar, he said, "I never go there. Nobody likes it there but there are no other options." All of this seemed very different from Cordoba and from what I knew of Buenos Aires.

Enrique walked me back to the center of the city and we chatted a little more about general life things before saying goodbye. I am so grateful to everyone at the house for speaking with me.

The next day I had an interesting experience at the Prisamata, the hostel where I stayed. The staff there could not be nicer or more helpful. I really enjoyed my time there, and I'm always really grateful to find a social atmosphere.

Won some poker one night

That morning, however, I stumbled into a conversation about homosexuality in the common kitchen/dining room. I wanted to make an early lunch and as I started to boil water for my pasta, I realized that the conversation at the table was about homosexuality and whether or not it was natural or right.

The thing is, I understand Spanish much better than I can speak it, so it was a little awkward for that reason. I'm not sure the men speaking knew I could understand most of what they were saying. It was also weird because although I was right there in the room, I had accidentally become a part of this situation.

Lujan, with whom I had spoken about my project, turned to me and incorporated me into the conversation, working as a translator. She was great about everything and I thought at first that I felt fine. After all, it was a familiar conversation. I had said and heard the same things over and over again with my dad, with lots of people.

It was strange because even though I've been traveling for quite a while now, I've been sort of insulated. My project is about queer community, so that is the community I seek out. Those are generally the people with whom I spend my time, queer people and travelers in hostels, most of whom, as someone told me on my very first day in Warsaw, are open and eager to spend time in places and with people who might be different.

It was odd to hear that argument in another place and in another language. Of course, I heard about the struggles and experiences of LGBT people as I traveled, but hearing about homophobia second-hand and being involved in a conversation in which someone wants to talk about interspecies mating and biblical passages are two totally different things.

It was a reality check for me. My guard was down, something that does not usually happen, and it became clear that I was not as ready as I normally was for this type of thing. I felt my hands start to shake a little, felt the familiar sort of shame that comes with these conversations, less now but much more often when I was younger.

I got moved out of my queer bubble and back into the world where people still said things about dogs and cats mating and where homophobia was treated as an acceptable piece of one's worldview, especially if Leviticus was involved. Anyway, I have no doubt that the guys arguing that I would suffer as a result of my sexual orientation (true, actually, thanks largely to worldviews like theirs) were nice people. I have no doubt. I was also reminded, however, of the gift of this year and of one of the main reasons I am pursuing my project in the first place.

It is amazing to be able to find a space where I do not have to be on guard all the time. That is what my own community at home gave me. That is what Pride parades gave me. A place or a day where everyone around me knows and understands and helps to make a barrier against that kind of nonsense that builds shame and self-loathing, where nobody will say, "Don't take it personally. There are lots of different opinions in the world," as if someone's condemnation of my sexual orientation and relationship were equivalent to a debate over which Pink Floyd album is best. I want to explore the ways that these communities, our communities, work around the world and what they give or don't give to people in a variety of contexts. The same with Pride.

Anyway, there was that. Similarly, later that night, a French visitor made a horrible and offensive joke about people in Argentina being able to marry their dogs if they wanted. Cute.

Later that day, I tried again with the office of the lesbian group because someone at the ATTA house confirmed the address but told me they are only there really late in the day, so I went to various museums around the city, including the Museo de Arqueologia de Alta Montana, which has two Incan child mummies on display. Salta generally is a beautiful city; it has colonial architecture and feels different from Cordoba or Buenos Aires.

From the Cabildo, a view of the main square downtown, the Plaza 9 de Julio

Finally I tried again at the Socialist Party office but nobody was there, sadly.

On my last day in the city, I did some more exploring, walking to San Bernardo Hill and taking a cable car to the top. It looks out over the whole city, and although it was cloudy basically the whole time I was in the city, it was still absolutely beautiful.

The thing is, I understand Spanish much better than I can speak it, so it was a little awkward for that reason. I'm not sure the men speaking knew I could understand most of what they were saying. It was also weird because although I was right there in the room, I had accidentally become a part of this situation.

Lujan, with whom I had spoken about my project, turned to me and incorporated me into the conversation, working as a translator. She was great about everything and I thought at first that I felt fine. After all, it was a familiar conversation. I had said and heard the same things over and over again with my dad, with lots of people.

It was strange because even though I've been traveling for quite a while now, I've been sort of insulated. My project is about queer community, so that is the community I seek out. Those are generally the people with whom I spend my time, queer people and travelers in hostels, most of whom, as someone told me on my very first day in Warsaw, are open and eager to spend time in places and with people who might be different.

It was odd to hear that argument in another place and in another language. Of course, I heard about the struggles and experiences of LGBT people as I traveled, but hearing about homophobia second-hand and being involved in a conversation in which someone wants to talk about interspecies mating and biblical passages are two totally different things.

It was a reality check for me. My guard was down, something that does not usually happen, and it became clear that I was not as ready as I normally was for this type of thing. I felt my hands start to shake a little, felt the familiar sort of shame that comes with these conversations, less now but much more often when I was younger.

I got moved out of my queer bubble and back into the world where people still said things about dogs and cats mating and where homophobia was treated as an acceptable piece of one's worldview, especially if Leviticus was involved. Anyway, I have no doubt that the guys arguing that I would suffer as a result of my sexual orientation (true, actually, thanks largely to worldviews like theirs) were nice people. I have no doubt. I was also reminded, however, of the gift of this year and of one of the main reasons I am pursuing my project in the first place.

It is amazing to be able to find a space where I do not have to be on guard all the time. That is what my own community at home gave me. That is what Pride parades gave me. A place or a day where everyone around me knows and understands and helps to make a barrier against that kind of nonsense that builds shame and self-loathing, where nobody will say, "Don't take it personally. There are lots of different opinions in the world," as if someone's condemnation of my sexual orientation and relationship were equivalent to a debate over which Pink Floyd album is best. I want to explore the ways that these communities, our communities, work around the world and what they give or don't give to people in a variety of contexts. The same with Pride.

Anyway, there was that. Similarly, later that night, a French visitor made a horrible and offensive joke about people in Argentina being able to marry their dogs if they wanted. Cute.

Later that day, I tried again with the office of the lesbian group because someone at the ATTA house confirmed the address but told me they are only there really late in the day, so I went to various museums around the city, including the Museo de Arqueologia de Alta Montana, which has two Incan child mummies on display. Salta generally is a beautiful city; it has colonial architecture and feels different from Cordoba or Buenos Aires.

From the Cabildo, a view of the main square downtown, the Plaza 9 de Julio

The outside of the Cabildo, which used to be a town hall but now houses a history museum.

Inside the Cabildo

Finally I tried again at the Socialist Party office but nobody was there, sadly.

On my last day in the city, I did some more exploring, walking to San Bernardo Hill and taking a cable car to the top. It looks out over the whole city, and although it was cloudy basically the whole time I was in the city, it was still absolutely beautiful.

Riding up in a cable car

View from the top

Also cacti

I took the stairs down from the top and ran into a guy from my hostel on his way up but also a guy from the hostel in Cordoba who had shared my room. Many travelers take the same route through Northern Argentina, although where they start and end may vary, so it was strange but not too strange to see him again.

Some of the stairs down.

The stairs are also set up as Stations of the Cross, so along with runners, there are people who pray as they climb.

I made it back to the hostel to finish packing and got ready for my bus to Mendoza.

This week I'm thankful for:

1. Sydney, Marco, and Lizi, who were so nice and welcoming and made my stay in Cordoba great

2. The welcome from Jose and the group in Salta. Thank y'all for feeding me and talking to me and making me feel at home so far away from home

3. A chance to remember exactly why LGBT community is so important to me and to others

4. As always, the various people who helped me when I was lost and made me feel comfortable in the hostels (especially Lujan, Aldi, and the rest of the group at the Prisamata) and a chance to explore new places